Growing up unexpectedly

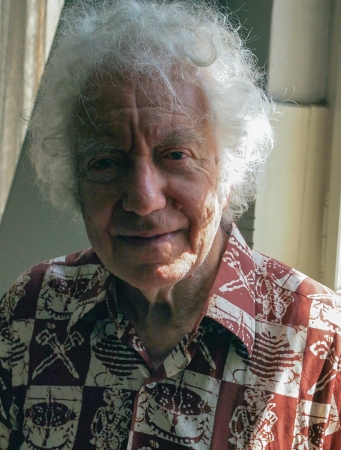

Another story from the Terezín ghetto is based on the memories of engineer Pavel Werner. Pavel was born in Prague on 3rd January 1932, but he grew up on Nerudova Street in Pardubice. His father (born 1890) was a deeply religious Polish Jew. He worked for Kudrnáč Náchod, which was later known as Rubena, as a travelling salesman. He represented the fi rm in Slovakia, where he travelled for a week and always returned home for just one day.

His mother (born 1905), née Raisensteinová, came from a naturalised Jewish family from Náchod, was a housewife and looked after Pavel and his younger sister Lenka (born 1935). Pavel recalls when one summer day his parents took them in a hired car to Zruč nad Sázavou to a summer fl at. Even nowadays, he is still reminded of this stay by a few uniquely preserved photos. Pavel went to a Czech elementary school in Pardubice and from the very beginning, he had private German lessons. He also attended Hebrew classes, but only until the arrival of Germans when Protectorate anti-Jew regulations came into eff ect. Yet, he started attending grade three of a sort of illegal school run by a grammar school student, Miss Krásová. However, he could not carry any school stuff since a child wearing a yellow star on his jacket caught on the way to a “private school” would be in grievous breach of the protectorate laws.

Pavel does not recall being especially aff ected by the anti-Jew laws. After the family had to leave their fl at in 1942 and move to Pražská Street to a house belonging to a Mr. Lochman on the outskirts of Pardubice, where they rented two rooms, Pavel was closer to nature and had more freedom. The family kept rabbits and they even had a tomcat, which was strictly forbidden to the Jews. At that time, the father was already unemployed and was doing only inferior unskilled work. When Pavel remembers his little sister Lenka, he recalls that she liked eating meat whereas he himself enjoyed sweet food. They had no meat at all, but he liked to think of the sweet semolina pudding. Supposedly, Lenka was a very good child and as he says they never argued, nor had any fights. However, whenever he heard the noisy marching Hitlerjugend boys approaching he would hide somewhere safe, as meeting them would have meant becoming the target of their hatred.

As time went by and the intentions of the Nazis were becoming clearer and clearer, Pavel tells us, all of a sudden, his mother started making sort of big crackers (they were big at least from a ten-year-old’s view) which he and his father wrapped in parchment. Not long after, the family went on the transport to the Terezín ghetto. The only thing that Pavel remembers is that Mr. Lochman lent them a four-wheeled cart which carried their allowed luggage limited by weight for the transport. Mr. Lochman followed them from a distance. After unloading the bags at the transport line-up point which was the business academy nearby the train station, Mr. Lochman inconspicuously crept up to his cart and left unnoticed without saying good bye. Much later, Pavel understood why it had had to be so.

After the night spent in quarantine at the business academy, they got on a passenger train. It took them to the station of Bohušovice and from there, they walked to Terezín. It was December 1942 and the Weber family involuntarily became inhabitants of the Terezín ghetto. Pavel, his mother and little sister were living at 21 Bahnhofstrasse and the father ended up in the former Hanover barracks. Today, you can read the names of children who had died at deportations. Pavel’s sister Lenka died of tuberculous meningitis shortly after becoming paralyzed in half of her body. The father was working in the joinery workshop at that time and Pavel recalls that he kept bringing pieces of wood in secret which he then used for making various shelves to exchange them for food. The mother became a watchwoman of dry toilets where she was responsible for cleanliness and also for the fact that everybody washed their hands with lysol. Pavel would often help his mum, which gave him, a boy, more social importance by being linked to such a responsible job. He remembers being involved in purely children’s activities. He sang in a children’s club but only one song, and as his father had been in Russian captivity somewhere in central Asia during the time of Austrian monarchy, he sang it in Russian.

The family escaped the fi rst transport bound east because Pavel was ill with otitis media. But 14th May 1944 came and they were reassigned to transport coded “DZ” bound for the camp Auschwitz-Birkenau. Pavel recalls not travelling in passenger carriages, but in “cattle” wagons and one of his unforgettable experiences was the faeces buckets that were overfl owing. After two days, they arrived at night, at their destination, a station sharply lit with spotlights, full of yelling SS-men and their raging dogs. The luggage, they brought with them from Terezín, had to be left in the wagons. After arrival at the railway ramp in Birkenau, Pavel and his father were put to camp BIIb, to the men’s wing where all of them got inmates’ numbers tattooed on their forearms. The mother ended up in the women’s wing but they would see each other fairly often as she volunteered for the distribution of soup barrels around the camp.

July 1944 came and selections started. Pavel and his father went together and knew what would follow. Naked, they approached an SSman sitting on a chair (later, Pavel found out that he was Mengele) who decided their fate with the thumb of his hand. Without uttering a single word, he sent Pavel to the “right side” from where he and some ninety other boys were sent to camp “D”. At the fi rst selection before Mengele, the father ended up in the other group which was much larger. God knows how he managed to come back to the crowd of men who had not gone through the selection yet, and he tried to repeat it. He stepped up and asked him to be sent to the same side where his son was standing. Mengele replied though: “You won’t be together anyway” and put him to the other side. It was the last time Pavel saw his father. Many years later, Pavel was close to talking to Mengele when he went on a business trip to Paraguay, but he had no idea that this wanted criminal was living there and most likely, he would not recognize him.

Pavel was in camp “D” in wing 13 until mid-January 1945 when Hitler’s men dissolved the Auschwitz complex. There was a group of 15 boys left out of the original larger group. They were told by the SS-men that the march was going to be long and challenging and that was why they would have to stay in the camp. The boys started shouting that they wanted to go too because they knew that in the other case the wardens would kill them. Indeed, they were assigned to the 80-kilometre death march to a little town of Wlodzisław Śląski (20 km northeast of Ostrava). If they had stayed there, however, they could have seen liberation by the Red Army ten days later.

Then, they were squeezed into open carriages where they were so tight that they had to be standing and those who fell, never stood up again. Their destination was another notorious concentration camp Mauthausen. There, they were stripped, given a cold shower and in freezing January weather, were forced into a house with nothing but a wooden fl oor. Only in the morning, they were given some rags to put on. After almost three weeks, Pavel and others were transported to another camp in Melk in Austria where he stayed until March 1945 and where they had to sleep in a circus tent for the lack of space. This was not the last stop; the next destination was a less-known camp Gunskirchen (near the town of Welz) where they got around mid-April. The place was in the middle of woods but the conditions there were unmatched by anything they had experienced until then. It was unconceivable how many prisoners were squashed in one place. There were fights over food and they had to drink water from puddles. If the imprisonment had lasted a few more days it is unlikely that Pavel would have survived. The Americans liberated the camp on 4th May and Pavel was quarantined at a nearby German military airfi eld where he stayed for nearly two months. Then, the Americans handed them over to the Soviets in a reception camp, hastily made at the site of camp Melk, where Pavel had been a prisoner some time before. Only the wardens had changed, the German ones were replaced by the Soviet ones. From there, they were taken to Wiener Neustadt from where Pavel and his mates Míša Kraus and Béďa Steiner set off on foot to Bratislava where they stayed for a couple of nights and eventually, they got on a train to Prague. When the train stopped in Pardubice at night Pavel said: “See you, I am getting off .” And this thirteen-year boy wearing a German uniform without any insignia was left alone at the station from where he and his whole family had left for Terezín almost three years ago.

At the station, there was a repatriation office where he reported and a clerk took him across the road to a little hotel where Pavel spent his fi rst night. In the morning, he was put on a lorry and taken to Albrechtice near Borohrádek in eastern Bohemia where he spent the summer holidays waiting in vain for his mother at least, to come back. Unfortunately, she had not survived the hell in Auschwitz. Pavel was given a Jewish guardian professor Eisner, who took care of everything else.

In 1950 Pavel passed his apprenticeship, as a shoemaker in Zlín. Then he started to attend the company’s business academy there as well but did not fi nish it and enrolled in the third year of a business academy at 5 Resslova Street in Prague – International Trade Course, and where he later graduated. Despite being a Jew, he was accepted (1953) at the University of Economics from where he graduated in 1958. After eighteen months of military service in Bor u Tachova, he worked as an interpreter in Olomouc and Hradec Králové. His work placement card led him to Prague where he started working for Motokov export company until it became Merkuria. He went on a business trip to Mexico in 1961, where he stayed for some time, and later also to Bolivia. After 1968 he kept working for the same company but only as a so called struck off communist party member who held no signifi cant position. After 1989, he worked for a company producing kitchen grinders in Skuhrov nad Bělou. As an expert in the fi eld of international trade, he managed not only national trade but above all, international trade and that helped him secure some fi nancial security for his retirement. He and his wife Jindra, née Mayerová from Hořice in Podkrkonoší, have a daughter Helena (born 1955), three grandchildren and one great-grandchild.

For Památník Terezín Luděk Sládek

Nesouhlas se zpracováním Vašich osobních údajů byl zaznamenán.

Váš záznam bude z databáze Vydavatelstvím KAM po Česku s.r.o. vymazán neprodleně, nejpozději však v zákonné lhůtě.