Life is not a game of tennis, where you get a second serve

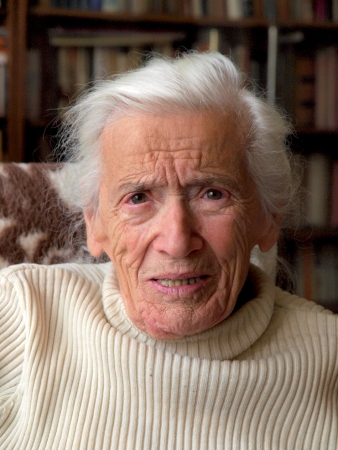

The life story of Eva Roubíčková, who was born into a German-speaking Jewish family, begins on July 16th 1921 in Žatec. Her father, Arnošt Mändel, a veteran of the First World War, taught at the local German grammar school. Her mother, Antonie, was a housewife; she brought up Eva and looked after her mother, Žofi e Wolfová, and her uncle, Arnošt Wolf.

After leaving junior school, Eva began to study at the grammar school. She used to enjoy skiing and had a similar love for tennis. But life is not tennis, where you can serve for a second time. Her carefree youth came to an end in 1938, when Eva was in the sixth year of grammar school. Although she had plenty of friends, this was a time when people were strongly infl uenced by anti-Jewish propaganda and she lost them one by one, until she was all alone, with a few other Jewish classmates, forsaken on the back bench. Her grandmother decided that Eva should leave school, and sent her to live with her relatives in Plzeň. She used to go to play tennis there, too, and this is where she met her future husband, Richard Roubíček, who had studied law and was then an articled clerk with a fi rm in Prague.

The pressure mounting up around the family was great, so Eva’s grandma decided that they should go to Prague for a time, until everything settled down. But things didn’t settle down. Her dad was pensioned off and came with uncle Arnošt to join the family on the last train out of Žatec. Their house remained empty. In Prague they had to make do on dad’s pension. Fate brought Eva to Richard again, who wanted her to go to England with him, but it wasn’t possible. Richard managed to leave just after the occupation of the Republic and travelled to England, where he soon joined the nascent Czechoslovak Independent Armoured Brigade. Eva remembers the exact day that Richard left. On the same day her grandmother committed suicide using lighting gas.

In December 1941 Eva, her mother and uncle Arnošt were deported to the Terezín ghetto. Her uncle signed up voluntarily, as Eva’s dad was in the pulmonary sanatorium in Pleš suff ering from tuberculosis, and Arnošt wanted to support the women. In the end, he was unable to help them, as in spring 1942 he ended up being transported to the Polish camp at Treblinka, where he was murdered by the Nazis soon afterwards. In summer 1942 Eva’s dad also arrived at the ghetto, and as a war veteran and in possession of the Gold Medal for Bravery from the First World War, he was protected from being transported to Poland. By that time Eva was travelling from the ghetto to work on a farm near Bohušovice. It is ironic that she looked after the sheep brought by the Nazis from Lidice, after they had burned the town to the ground. This is where she met the railwayman Karel Košvanec, who kept hidden provisions for the prisoners in Terezín on the land she worked on. Eva found his fi rst two packages and got them through the gendarme checks and into the ghetto. However, she was stopped when carrying the third package through and questioned by Janetschek, the leader of the Terezín gendarmerie, who was executed after the war for collaboration. In one of these questioning sessions she made a mistake which still pains her to this day. Košvanec had put an onion into the package, which in the eyes of the gendarmes could only have come from the farm. She didn’t want to betray Košvanec and knew that one of the gendarmes occasionally allowed her friend Benny Grünberger to bring something in, so she said that she’d got the onion from him. But the gendarme denied everything and Benny was transported to the east as punishment, never to return. They tortured Eva and locked her in the Terezín gendarmerie prison, where she remained until her father intervened to have her released. Karel Košvanec continued supplying provisions until the ghetto was liberated. On October 14th 1944 Eva’s family were put on a train and transported to Auschwitz. Eva wanted to go with her parents, but Rahm, the commander of the camp, decided she could not. Eva doesn’t know why, but as soon as they arrived, her parents were sent to the gas chambers.

Eva survived to see the camp liberated, and on May 5th 1945 she even met Košvanec, but as she had come down with typhoid fever, she had to spend another month in quarantine. Upon returning to Prague she realised that she had nothing and that all her relatives were dead. She thought about what to do next. As she had looked after the mother and sister of one of Richard’s friends, she visited one of his non-Jewish relatives and found out that Richard had visited shortly before, but had had to return to his unit in Šumava. So she took his address and wrote to him. Two days later Richard appeared on her doorstep, and in three weeks they were married. Now Eva is 89 and has two children, four grandchildren, and one great-grandchild. Her husband, however, died at the age of 83. Eva used to keep a diary before the war, and continued to do so while she was in the ghetto. From the shorthand notes of her experiences, a book was made, entitled “Terezín Diary 1941–45”, which was published in Czech in 2009 with the help of the Jewish Community in Prague, Vojtěch Blodig from the Terezín Monument, and Ondřej Klípa.

Luděk Sládek

Nesouhlas se zpracováním Vašich osobních údajů byl zaznamenán.

Váš záznam bude z databáze Vydavatelstvím KAM po Česku s.r.o. vymazán neprodleně, nejpozději však v zákonné lhůtě.